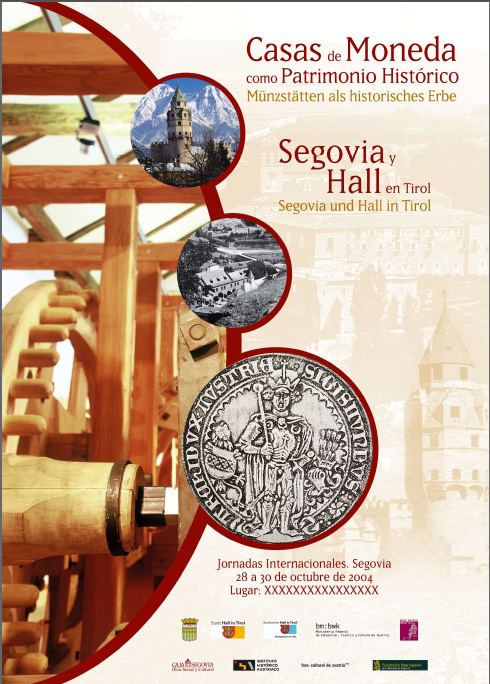

Despite having a network of mints in his territories in the second half of the 16th century, Philip II, recognising the importance of the new minting technique, decided to establish a new Mint. Its history began in late 1580 with Philip II's decision to introduce the new technique of roller minting coins in his kingdoms. He had received information about a novel hydraulically operated machine that had been perfected in the 1560s in Tyrol and had been minting coins since 1567 at the mint in Hall in Tyrol, owned by Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol, Philip II's cousin. The new device guaranteed a better quality of coins, produced mechanically and more quickly, rather than by hand with a hammer, thus reducing personnel and costs, which resulted in significant savings. In 1582, while Philip II was in Portugal, the request was formalised, the price of the device was set, and the method of shipment and the architectural and technical requirements for its installation were determined.

This industrial plant, as we would call it today, consisted of a building, hydraulic installations – a canal and wooden wheels with their axles – and the machinery itself. The plan was that, while the machine was being built at the mint in Hall in Tyrol, the necessary structure for its installation would be prepared in Spain. Everything was to be completed by the time the machinery arrived, which was ultimately gifted by Archduke Ferdinand to his cousin Philip II.

A group of skilled craftsmen and workers was therefore sent from Tyrol to Spain. In 1583, it was decided that Segovia would be the site of the new Mint, where Philip II had purchased a flour and paper mill on the banks of the Eresma River. At the end of that year, work began under the supervision of the royal architect Juan de Herrera, and in 1584 the first building of the new Mint of Segovia and the hydraulic installations were completed, in particular a wooden canal that carried water from the river to the wheels that would drive the machinery. In 1585, after a long journey, the machinery arrived in Segovia, accompanied by a group of coin makers from Hall in Tyrol, who put the royal machinery into operation. The following year, regular production of coins of a quality hitherto unknown in Spain began, continuing until the second half of the 18th century when flywheel presses were introduced. In 1868, the Segovia Mint closed its doors.

The town of Hall in Tirol is located 10 km east of Innsbruck, the capital of Tirol, in the Inn River valley. It dates back to the Middle Ages and celebrated its 700th anniversary as a town in 2003. In the same year, the renovated Hall Mint Museum (Münze Hall) opened its doors. The recovery of 16th-century technology, which in the case of the Hall Mint has been achieved with the reconstruction of the roller mill, is now in full swing.

In 1477, Sigismund the Coin-Rich (1446-1490), Archduke of Austria and Count of Tyrol, established his mint in Hall, a key location where the trade routes from the east and west and north and south crossed. At that time, Hall was more important than Innsbruck, now the capital of Tyrol. in a city that was at that time more important than Innsbruck, today the capital of Tyrol. From 1482 onwards, a new monetary system developed in Hall, culminating in the minting of the silver ‘Taler’, a coin that gained enormous importance from the 16th century onwards. A decisive factor was that not far from Hall, in the mountains near the town of Schwaz, there were rich silver mines that provided the raw material. With the help of the new mint built in Tyrol, which replaced hammer minting in Hall in 1571, large quantities of silver were minted at the end of the 16th century. The mint in Hall remained in operation for 180 years, until the time of Empress Maria Theresa in the 18th century. Then, around 1750, it switched to wheel minting. The history of the Hall Mint ended in 1809, during the Napoleonic Wars, when the Hall Mint was closed during the occupation of Tyrol by Bavarian troops, allies of the French, during the struggle of the Tyroleans, led by Andreas Hofer. Hasegg Castle then became a building that had nothing to do with its past, and it was not until 1975 that the process of restoration began.